What I hope to achieve through the pedagogies of student-created digital media projects and 3D choice is to improve student engagement and creativity in STEM classes. To do this requires a basic understanding of both; they deserve an entire book each to adequately discuss, and I hope to write such books someday. For the purposes of this discussion, I will attempt to be as brief as possible to outlay current theories of student engagement.

Student disengagement can be studied at two levels: at the level of disaffection with daily classroom activities through demonstrating boredom, avoidance, and rebellion; and at the level of school and society. Disengaged students are at much greater risk of dropping out, with all the attendant social problems of poverty, higher rates of violent crime, substance abuse, bad health, and greater dependence on public assistance (Henry, Knight, & Thornberry, 2012; Wang et al., 2019).

Theories of student engagement rarely look beyond the immediate classroom to examine the effects of larger systems such as peers, family, or community. One of the few examples is a study by Crawford, Snyder, and Adelson (2020) that uses Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977 & 1986) to analyze underrepresentation of minority students in gifted education programs. Another example is an extensive review of literature by Lawson and Lawson (2013) that explores engagement as a dynamic, synergistic process occurring between students, school, and society.

There are many influences on a student, and it is the purpose of this section to develop a model which synthesizes students’ engagement in the classroom microcosm with their involvement in larger society, then demonstrate how this expanded model has important implications for the current study.

Definitions of Student Engagement

Kuh (2009) defines student engagement as “the time and effort students devote to activities that are empirically linked to desired outcomes of college and what institutions do to induce students to participate in these activities” (p. 683). This definition can be broadened to include K-12 education. Some of the desired educational outcomes include student success and development, satisfaction, persistence, academic achievement, and social and civic involvement (Groccia, 2018). This definition leads to questions about why these outcomes are desirable and whom they benefit.

Axelson & Flick (2010) define student engagement as “how involved or interested students appear to be in their learning and how connected they are to their classes, their institutions, and each other” (p. 38), attesting to the importance of student interest, social milieu, meaningfulness, and connectedness to the subject matter.

Skinner & Belmont (1993) explain that engaged students demonstrate several behaviors including selecting challenging tasks at the border of their abilities, initiating action when given an opportunity, showing intense effort and concentration in the completion of a task, and displaying positive emotions of enthusiasm, curiosity, and interest.

Commonalities between these definitions show that student engagement requires sustained involvement, time, effort, and connection with learning activities which leads to desired educational outcomes, some of which are measurable and behavioral while others are cognitive or emotional. Lawson and Lawson (2013) discuss the agentic nature of engagement: students choose what they will engage with.

Theoretical Models of Student Engagement

Schlechty’s five levels of engagement. An early theory of student engagement by Schlechty (2011) looked at five different levels of involvement and what constituted true student engagement, beginning with students who actively rebel against classroom activities and cause disruptions to the lesson. Other students avoid completing the lesson or avoid attending class but do not actively rebel. A third group shows ritual compliance with the requirements of the activity to escape punishment or negative consequences but will soon give up if any challenge occurs. A fourth group appears to be engaged but are only strategically compliant to achieve good rewards aligned with the lesson (such as grades) but will not internalize the lesson. The fifth group shows true engagement, where their efforts and interests are completely aligned with the lesson; they will persist in the activity because they see the activity as inherently beneficial (Schlechty, 2011).

Doing, thinking, feeling. Various studies (Schneider et al., 2016; Crawford, Snyder, & Adelson, 2020; Juuti et al., 2021) agree that engagement is much more than sitting quietly in a desk working on an assignment. Quiet students may only be showing strategic compliance and feigning attention (Schlechty, 2011). An emergent model of engagement (Corso, Bundick, Quaglia, & Haywood, 2013) is comprised of three modes: behavioral, cognitive, and emotional. Certain behaviors such as attending school, completing assignments, and participating in activities are essential for engagement. To be fully engaged requires a cognitive dimension as students not only show attention but open their minds to learning and meaning-making through their experiences. It also requires an emotional dimension of caring about the lesson content and feeling safe so that learning can occur. From a student perspective, the three dimensions of behavioral (doing), cognitive (thinking), and emotional (feeling) must all align for true engagement. Other models such as Schneider et al. (2016) and Csikszentmihalyi (1996, 2014) operationalize engagement as students experiencing high levels of challenge, skill, and interest leading to optimal learning and creativity.

Student, teacher, content. A more sophisticated model of student engagement is proposed by Fisher et al. (2018). In this model, shown in Figure 1, three aspects of a quality lesson intersect to create engagement. The first aspect is the student, who must show the types of behaviors, cognitions, and emotions necessary for learning. The second factor is the teacher, who must bring effective practices and knowledge to the classroom for learning to occur. The third factor involves the subject content itself. Interesting and challenging content is essential to engagement.

It is in the overlaps between these three factors that the model shows insight. For effective learning to occur, there must be positive, supportive relationships between the teacher and the students. A study of 14 teachers and 133 students in grades 3-5 by Skinner & Belmont (1993) shows that a supportive student-teacher relationship is essential for student engagement in classroom activities, and that when such supportive relationships are absent, students become disaffected and unmotivated. According to Noddings (2005), these relationships should be based on caring. A classroom culture must be established where teachers care for their students as learners and students learn to care about themselves, their fellow students, teachers, humanity, and the natural world.

Where the content and students overlap, there must be challenging, meaningful, and relevant content which allows for the right balance of student skill with content difficulty. Csikszentmihalyi (2014) suggests that where this balance is achieved, a state of flow builds where learning seems effortless and time is suspended. Students who experience flow are more likely to enjoy and remember the lesson (Csikszentmihalyi, 2014).

The third interaction occurs between teacher and content. Teachers must be enthusiastic experts not only in their content areas but also in the appropriate theoretical frameworks and practical pedagogies required to bring the content to life. This clarity between the teacher and the content, along with supportive teacher-student relationships and content challenge, interact to bring true engagement.

Outside influences. In the Fisher et al. (2018) model the microcosm of the classroom is the center of the learning experience, but students learn in other environments as they engage with subjects, ideas, and influences outside the classroom. Students have agency in how and what they choose to engage with. A theoretical model by Groccia (2018) looks at student engagement at the collegiate level and identifies several educational arenas where students may choose to engage, as shown in Figure 2. These include involvement with other students in clubs, in teaching as teacher assistants and peer tutors, in learning their subjects in and out of the classroom, with the community through internships and service activities, in research as lab and research assistants, and with faculty and staff. As they engage, they bring their behaviors, feelings, and thoughts to the challenges of their chosen arenas.

Critiques of engagement theories. Despite efforts of schools to incorporate constructivist strategies into their classrooms, student disengagement and disaffection still exist (Henry et al., 2012). Most research into student engagement has focused on neurotypical, able-bodied, Caucasian, middle-class students (Vallee, 2017). Recent criticisms of this research (Zepke, 2017; Macfarlane & Tomlinson, 2017) suggest it has been too uncritical of the purposes behind the drive for increased student engagement, especially at the collegiate level. Zepke (2017) argues that higher education has become enslaved by the forces of free market economics and neoliberal philosophy. Education, especially college education, is increasingly viewed as a means of providing consumers and new entrepreneurs as the driving engine of market growth. Getting into the best colleges (even the most elite high schools) is seen as a competitive advantage and universities are no longer viewed as the source of liberal activism, democratic thought, or as a public commons. They are a consumer product, a resource to be used. In Zepke’s view (2017), student engagement initiatives are a means to manipulate students into conforming to neoliberal ideals. He advocates for a more critical social reconstruction theory of student engagement that exposes the inherent oppression and disenfranchisement behind engagement programs, which lead to the frustration and rebellion of students who are left out of consideration for the market economy.

With these criticisms in mind, a more complete model is needed which takes a systemic look at student engagement and disengagement.

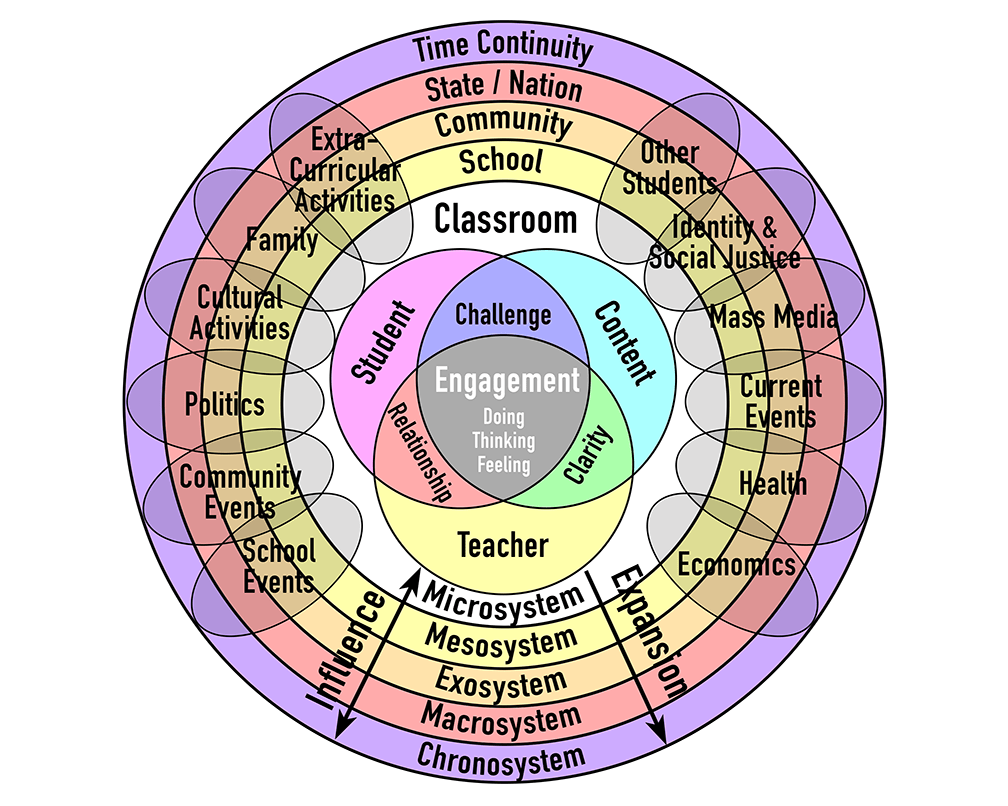

A Synthesis Model. The various models of student engagement discussed thus far can be combined with Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1977 & 1986; Guy-Evans, 2020). The ontological assumption is that student learning is influenced by more than the classroom, similar to the findings of Lawson & Lawson (2013). This theory situates the student inside a series of five nested systems beginning with the local microsystem, which is the student’s immediate surroundings (such as the classroom), and spreading outward to larger systems including the mesosystem, which can be considered the local environment, the school or neighborhood of the student; the exosystem, which is the community within which the student is embedded; the macrosystem or larger culture and state/nation in which the student resides; and the chronosystem, or changes that occur over time.

Figure 3 diagrams this synthesis model within the five concentric rings of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977 & 1986). Inside the classroom or microsystem, the student is engaged in educational activities at an intersection of student, teacher, and content factors and through doing, thinking, and feeling as discussed by Fisher et al. (2018). The Groccia model (2018) has been adapted from a higher education setting to one more closely aligned with the influences on a K-12 student, which cross over through the chronosystem, macrosystem, exosystem, and mesosystem to impinge upon the classroom microsystem, shown in the synthesis model as gray ellipses. They can occur locally or nationally, can have indirect or direct influence over the classroom microsystem and daily lives of students, and can change over different time scales.

Influences on a student’s daily life and the microsystem of the classroom include school rules and funding; extra-curricular activities such as clubs or drama; cultural activities including holidays and religious events; political and legal influences such as local political parties, candidates, and policies; community influences and events; family influences including socio-economic status; the influences of peers, friends, and other students; issues of self and gender identity, social justice, systemic racism, bullying, and oppression; the increasingly invasive influences of media in classrooms including electronic games and social media; anxiety-provoking current events; personal and family health issues including the effects of COVID-19; and economic and monetary issues.

These influences in a student’s life overlap each other and are not mutually exclusive; mass media can affect identity and a pandemic becomes an important current event. The need to get a job to support family prevents a student from participating in school sports or other extra-curricular activities. This is why the gray ellipses overlap each other while also intersecting across all five levels of Bronfenbrenner’s model.

Students can engage in many arenas simultaneously. They live within a complex interconnected web of concentric systems and overlapping influences that affect their lives and change their ability and interest to engage in classroom activities. Analyzing these influences helps us understand why some students disengage from classroom activities despite highly meaningful, student-centered lessons and content, positive student-teacher relationships, and appropriate challenge. They might already be fully engaged in other activities and in other arenas that provide the challenge they need or have problems and issues that pull their attention and engagement away from the classroom. Lawson and Lawson (2013) specify that student engagement, when viewed systemically, is a multilayered transactional process between student perceptions of the benefits of engagement, the conditions in which the student is acting (such as teacher and content factors), and student dispositions toward or against engagement in particular situations.

The outside influences that affect students also affect teachers and content, the other two components of the Fisher et al. model (2018). Parent committees, school boards, and other local and state groups influence the type of textbooks used in classes and the standards that are approved, modifying the content. Teachers do not hang themselves in the closet when they return home in the afternoon (contrary to many students’ apparent beliefs) but are active in the community and the larger macrosystem. Whenever outside rules, school district and state regulations, and other factors become oppressive and controlling, the ability of teachers to fully engage in teaching is curtailed.

The mesosystem of students can be seen as a variable zone that interphases between a student’s immediate surroundings (the classroom) and larger influences in the exosystem and beyond. Young students have a limited mesosystem; they may only be aware and able to function in a localized environment of the street they live on, their school, and the local playground. As students learn and mature, their mesosystem expands as they become aware of larger influences in their lives. They become able to function as part of a community and eventually take their place as adults in a macrosystem of full responsibility that accepts changes over time. This mesosystemic expansion is a natural consequence of learning, growing, and maturing and is like Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development or ZPD (Harland, 2003; McLeod, 2020b). Mentors, teachers, and peers assist students in expanding their ZPDs or mesosystems, becoming more capable.

For this natural mesosystemic expansion to occur, however, students must actively engage in the influences in which they are embedded. Without engagement there can be no growth and no learning, and they will never reach the levels of maturity and full responsibility required of adults. Being an adult is therefore not a matter of age or physical maturity; it is achieved through full engagement with the systemic influences of one’s life. For example, for adults to become fully responsible voters, they must civically engage by actively seeking out information on different political opinions, candidates, and issues. As students’ mesosystems expand, what they consider as their “neighborhoods” can grow until it encompasses the entire world; what happens in Timbuktu or Taiwan or Turkey in terms of climate change or injustice is just as personal to them as if it occurred next door. They become global citizens.

Applications of the Synthesis Model to Educational Practice

The major educational implication of this synthesis model is that student engagement is more than a local classroom phenomenon. The process of education can be seen as preparing students to widen their spheres of experience and expand their capabilities into broader systems. As students engage in the various influences around them, they grow into capable, responsible adults with personal agency to act. The classroom provides an interface for life-long engagement with the world.

True engagement involves doing, knowing, and feeling through the interaction of student, teacher, and content with any of the influences in the model. As an example, for students to engage in an extra-curricular sport, they must have appropriate challenge to match their skills and achieve an optimal level of flow for peak performance. They need supportive relationships with their coach, and they need a coach with clarity of experience to provide high expectations.

Although it seems that the influences that surround a student only work from the outside in, affecting what happens in the classroom, it is true that the influences work both ways. Individual students can have an impact on the larger world, and what a student learns in the classroom has a long-term chronosystemic effect on that student’s life. Ultimately, if enough students take a stand on an issue, they can make a positive social change. They can reconstruct the society around them.

Applying this idea to a specific instance, let us consider students’ learning about climate change in an environmental science class. If the teacher only considers the microsystem of the students’ classroom even an exceptionally well-done, student-centered lesson will not fully engage students. For that, students need to turn outward and become agents of change. They must invest behaviorally, emotionally, and cognitively in improving their community through meaningful project-based or problem-based learning such as clean-up campaigns, public awareness activities, or some other fully engaged learning experience designed to acquire responsibility for their environment. Put simply, fully engaged learning involves students working to change their embedded systems; it is all-in learning.

It might be argued that this is an unrealistic expectation for education. After all, how can students in a single classroom affect meaningful change in the world over time? Yet individual students have done just that. They have and will change the world, and that is the only way the world can change: one student at a time. It must start somewhere.

Conclusions

The synthesis model of student engagement incorporates several partial models (Fisher et al., 2018; Groccia, 2018) into a more complex and systemic whole, with students embedded within the concentric rings of Bronfrenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model (1977 & 1986) as they engage within their classroom microcosms. This model recognizes that challenging and meaningful subject content is required for engagement, as are supportive relationships between students and teachers based on respect, trust, and open communication. Teachers must have pedagogical experience, enthusiasm, and content knowledge. When these factors are present, student engagement is greatly enhanced.

Yet it is not guaranteed. Numerous outside influences impinge on students’ daily lives. Oppressive systems, family issues, disenfranchisement of marginalized groups, and the effects of war, climate change, systemic racism, bullying, etc. affect how well a student can engage in classroom activities. Without considering these reasons for disengagement, we will never succeed in preparing students to reconstruct society (Zepke, 2017).

References

Axelson, R. D., & Flick, A. (2010). Defining student engagement. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 43(1), 38-43.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513-531.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723-742.

Corso, M. J., Bundick, M. J., Quaglia, R. J., & Haywood, D. E. (2013). Where student, teacher, and content meet: Student engagement in the secondary school classroom. American Secondary Education, (41(3), 50-61.

Crawford, B. F., Snyder, K. E., & Adelson, J. L. (2020). Exploring obstacles faced by gifted minority students through Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological systems theory. High Ability Studies, 31(1), 43-74.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: Harper Collins.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Flow and the foundations of positive psychology: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. New York: Springer.

Fisher, D., Frey, N., Quaglia, R. J., Smith, D., & Lande, L. L. (2018). Engagement by design: Creating learning environments where students thrive. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Literacy.

Guy-Evans, O. (9 Nov. 2020). Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. SimplyPsychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/Bronfenbrenner.html.

Harland, T. (2003). Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development and problem-based learning: Linking a theoretical concept with practice through action research. Teaching in Higher Education, 8(2), 263-272.

Henry, K. L., Knight, K. E., & Thornberry, T. P. (2012). School disengagement as a predictor of dropout, delinquency, and problem substance use during adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 156-166.

Juuti, K., Lavonen, J., Salonen, V., Salmela-Aro, K., Schneider, B., & Krajcik, J. (2021). A Teacher- researcher partnership for professional learning: Co-designing project-based learning units to increase student engagement in science classes. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 32(6), 625-641.

Kuh, G. D. (2009). What student affairs professionals need to know about student engagement. Journal of College Student Development, 50(6), 683-706.

Lawson, M. A., & Lawson, H. A. (2013). New conceptual frameworks for student engagement research, policy, and practice. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 432-479.

Macfarlane, B. & Tomlinson, M. (2017). Critiques of student engagement. Higher Education Policy, 2017 (30), 5-21.

McLeod, S. (26 July 2023). Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of cognitive development. SimplyPsychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/vygotsky.html

Noddings, N. (2005). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education, 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

Schlechty, P. C. (2011). Engaging students: The next level of working on the work. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schneider, B., Krajcik, J., Lavonen, J., Salmela-Aro, K., Broda, M., Spicer, J., Bruner, J., Moeller, J., Linnansaari, J., Juuti, K., & Viljaranta, J. (2016). Investigating optimal learning moments in U.S. and Finnish science classes. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 53, 400–421.

Wang, M. T., Fredricks, J., Ye, F., Hofkens, T., & Linn, J. S. (2019). Conceptualization and assessment of adolescents’ engagement and disengagement in school. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(4), 592-606.

Zepke, N. (2017). Student engagement in neoliberal times: Theories and practices for learning and teaching in higher education. Singapore: Springer Nature.

Leave a comment