As we approached the fall of 2023, I had hoped to have my dissertation proposal ready to go and to gain approval before our first Science Communication competition began, but that was not to be. I was a bit over-optimistic on how long it would take me to wrestle through the theoretical and practical implementation details in time for my committee and the IRB to give approval. This meant that I wouldn’t be able to count this first pilot program toward my dissertation, yet we still needed to go through with the contest because it was already advertised and because we needed the data to see if we were on the right track as a planetarium. The education department here has never tried anything like this, at least within institutional memory.

So we went ahead with the contest as a pilot program, treating it as a dry run for an improved program in the fall of 2024. This would give me the time I needed to truly get my proposal in shape and approved without pushing deadlines while still seeing if the contest would actually work.

Utah would be experiencing an annular solar eclipse on Oct. 14. Part of a grant we received for the eclipse was to send out solar eclipse glasses to all 6th grade students in Utah. I had spent much of the summer managing this program, helping to get the glasses boxed, labeled, delivered and/or mailed out. I got approval to use this opportunity to include flyers on the contest and also advertised it through the Utah State Board of Education’s upcoming events newsletter. The glasses were sent out to schools and not to individual teachers, so it provided some information and exposure but not much of a call to action; only a few teachers expressed interest through the mailed flyer.

I presented on 3D choice at the Utah Science Teaching Association’s annual conference on Sept. 15 and talked about the contest, then manned our table in the dealer’s room and signed up as many teachers as I could, about 25 altogether. I also got a few to sign up by manning a desk at the STEM fest at South Towne Plaza. Of these, only five continued to express interest and answered my email inquiries. But this would be enough, and included one private school, one rural school, a charter school, and two teachers in a regular public school. Altogether, 92 students attempted projects of which 75 completed all parts, including a project with peer reviews and revisions, pre-and-post tests, parent-signed consent forms, and Google form project descriptions.

This was meant to be a first approximation and an experiment; there were differences in how the teachers applied the instructions, and I allowed fine art and physical 3D sculptures as media categories so as to see how many students would choose digital media if allowed the option. Not many, as it turned out: most students chose to create hand drawn illustrations or posters or to create 3D sculptures (such as styrofoam solar systems). Many of these were certainly creative and showed high engagement and content mastery, but they did not demonstrate my dissertation’s goal of student-created digital media (SCDM) projects. Some teachers indicated that students began to look at the browser-based software, but gave it up as too hard to learn and returned to hand-drawing instead. Those that stuck with it generally had more creative projects and did better in the competition as there were fewer projects to compete against.

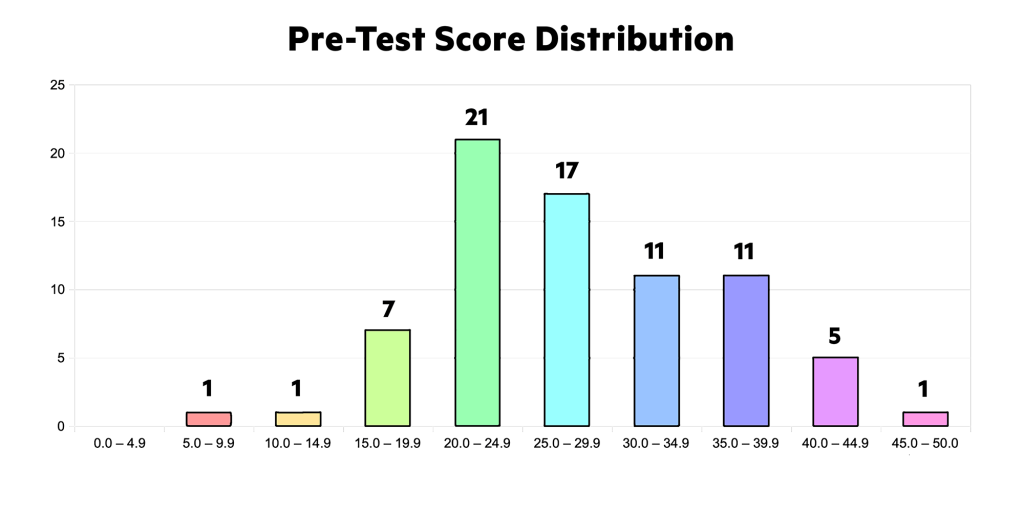

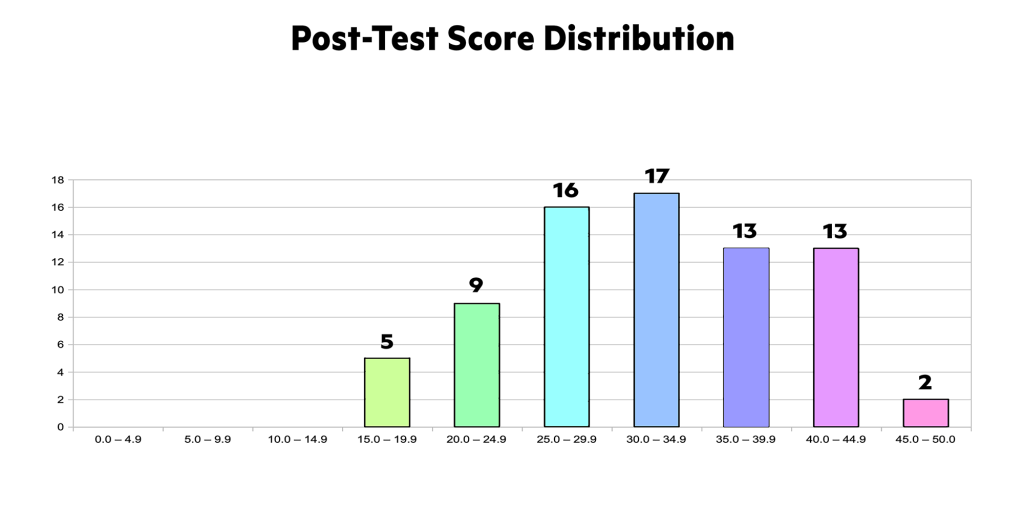

Looking at the pre-and-post test scores, the overall student average raised by 7.9%, which was significant to the p < 0.0005 level for a one-tailed paired t-test. Interpreted, this means that students really did learn about space science between taking the pre-test and the post-test. Since I did not have non-project comparison groups, it is impossible to say whether this gain is due to the project (qualitative data supports this) or just due to other learning or maturation. I will need comparison groups in the final dissertation research. No teachers wanted to do a non-participatory control group.

I had the students fill out a separate Google form questionnaire on what they learned, what challenges they overcame, and what they would do differently. Teachers also filled out an extensive Google form on what they saw regarding engagement, creativity, learning, etc. Students reported various time-on-task estimates with an average of about 9 hours and a median of 4.0 hours. I also interviewed two of the teachers and gained insights into the process and what to improve for next year. In addition, for evaluating the projects and providing feedback so that students could improve and revise their projects, I had at least three peers see each presentation and fill out a peer critique Google form.

Overall, looking through these qualitative responses and interviews, I can see need for the following changes:

- I need more detailed time-on-task questions with number of hours specifically emphasized. Answers were too vague and ranged all over the place, even those that took the question seriously.

- I must include more questions on the lived experiences of the teachers as they implement this project, with interviews of all of them to gain the phenomenological data I will need. What little I did get this time was excellent; getting interviews of all the teachers will be the major source of qualitative data for this next phase.

- I need to find at least five teachers or classes to be a control group, taking the pre-and-post tests but not creating projects. There isn’t a lot of incentive to do this, but I need to compare the learning that occurs with teachers normally due for their space science units with what happens as a result of the contest, otherwise I can’t really draw conclusions. There were a few students who took both tests but did not do projects (most due to parents not signing consent forms) so I could at least see the spill-over effect – these students did raise their test scores but not as much as students who actually created projects. Since the non-project students were in classes with the project students, they saw the presentations and filled out the peer review forms, so they learned from the projects as well. I did not have classrooms that took the tests but did not participate in the projects.

- For the peer critique Google form, I asked students to comment on each of six characteristics including scientific accuracy, concept mastery, creativity, quality, software or artistic skill, and communication. This was a bit much for them, and many of the comments were minimal or just the same comment repeated. I will need to ask only one comment and cut the characteristics down to five, combining scientific accuracy and concept mastery.

- Most importantly, the methods I tried for teaching students how to use the software largely didn’t work. Most students reported not even looking at the 16 flipped training videos I created; they were 20-30 minutes long, too long for a Generation Z or Alpha student to want to sit through. I need to re-edit these down to 2-3 minutes each and add gamified elements to improve motivation and to provide a measure of training completion, working this in as a requirement and cutting out the fine art categories of media. I am calling the new videos Digital Media Micro Lessons (DMMLs) and have eight planned as required training, then a semi-structured choice list for each software package. Once a student has completed the required and the requested number of optional videos, they will be certified in that software and able to move on to creating their science communication project. I will certify them by having them include a feature in their media based on a hidden message across the videos, such as a smiley face in a video project. This will be done by having occasional flashing letters that the students can write down and which will spell out their instructions. Kind of like “A Christmas Story” and “Be sure to drink more Ovaltine.”

These are the main lessons I learned from the pilot program. Now I need to get the final proposal approved (it is almost there) and we will be good to go for the full contest, which we are now called the Cosmic Creator Challenge.

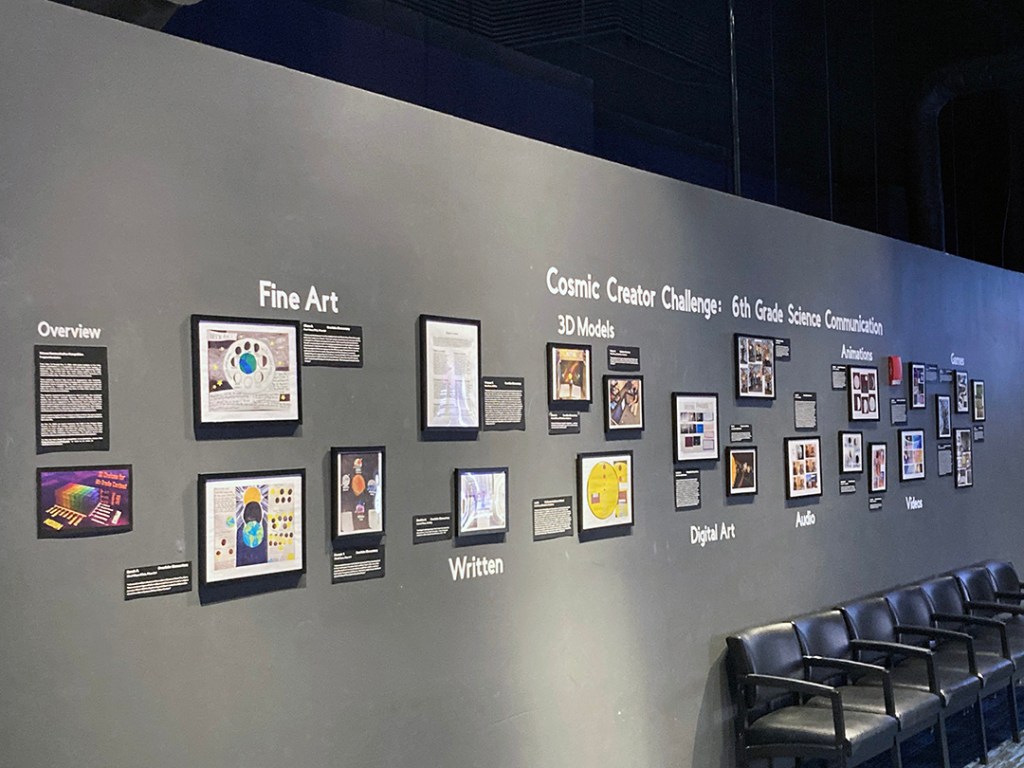

Once the winners of this last pilot program were determined, I sent an email to each teacher and announced that we would have an award program at Clark Planetarium. This was held on Feb. 15, 2024 for the first, second, and third place winners of each of eight categories. I asked the winning students to prepare a 2-minute verbal description of why they chose their topics and approach, what they learned, what challenges they overcame, and why they thought their projects were creative. We held a pizza dinner with fruit and veggie trays and had the ceremony in the Hansen Dome Theatre, with over 100 people attending. The winning students were allowed to bring their families, and we had most of the teachers as well. We gave out certificates to the 2nd and 3rd place winners and trophies to the first place winners in each category, with a nicer trophy for Best of Show, given to a student who developed their own board game with 3D modeled and printed game pieces and a DTP instruction manual. He put it all together in a nice box with cover image so that his teacher could use it in future years. He chose the topic of the scale and proportion of the solar system and distances between planets.

The student descriptions were printed out in white letters on a black background on cardstock and the winning projects printed out and placed in frames. I also learned how to use a Cricut machine to create the lettering with self-adhesive vinyl letters. All of this was placed on a wall on our third floor near the restrooms where people can readily see it to help drum up excitement for 2024’s Cosmic Creator Challenge.

Overall I can say quite definitively that this contest demonstrated enhanced student creativity along with engagement and content mastery. That was the goal. The students were able to apply three-dimensional choice effectively, and the final results were very encouraging. We have proven that this contest will work; I know that I will get good results for the final research. We are treating this just like the student projects, as a work in progress; I look forward to the next iteration.

As I have visited schools during the year, I have actually visited three of the five participating schools and talked with and observed the students at more length. For example, at Circleville Elementary there were two students who participated and one did a photographic project on phases of the moon. As I taught this phases in her class, she was able to answer all of the questions easily. In Overlake Elementary in Tooele, one of their special education students showed more interest in this project than he had shown in most other activities according to his teacher, and spent quite a bit of time on his poster of the seasons. As we visited his classroom, he was surprised that I knew his name. He participated very well in answering our questions and as part of the activities. So there is evidence that this program benefited not just the winning students but others as well.

Keep your eyes on this website for new rules, the Digital Media Micro Lesson links, and other tools for the upcoming 2024 Cosmic Creator Challenge. It’s going to be fun!

Leave a comment