Many theories have been proposed to explain creativity or to at least attempt to define it. This post will provide short summaries of twelve of the most common definitions proposed over the millennia and end with some barriers to creativity, how to overcome them, and implications of these theories for educational practice.

Anciently, the Greeks and Romans believed that creativity was a gift from the gods in the form of a personal daimon or genius. The Muses communicated the will of the gods to one’s daimon, which acted as a push toward greatness. The daimon was seen as an irrepressible drive; if one tried to deny it and avoid it, it would drive one mad or cause one to self-destruct. It was one’s personal destiny and fate, and it was the responsibility of each person to find out what that fate was, accept it, and pursue it. It was Socrates who stated the Greek imperatives as carved into the Temple of Apollo at Delphi: know thyself and become thyself. The daimon was a potentiality that required expression and actualization.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, creativity is a talent bestowed at birth that one is expected to magnify for the benefit of humanity. This is shown in the Parable of the Talents taught by Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew – the master expected his servants to take the talents of silver and put them to the exchangers, to make more from them.

Later theories of creativity saw it as one of many innate traits, a part of one’s personality determined at birth by genetic predispositions. Creative persons could be identified by comparing them to a list of the traits of creative people or by taking a series of creativity tests, such as the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking; if you had the traits, you had creative potential. If you didn’t show the characteristics, you were unlikely to ever develop creativity.

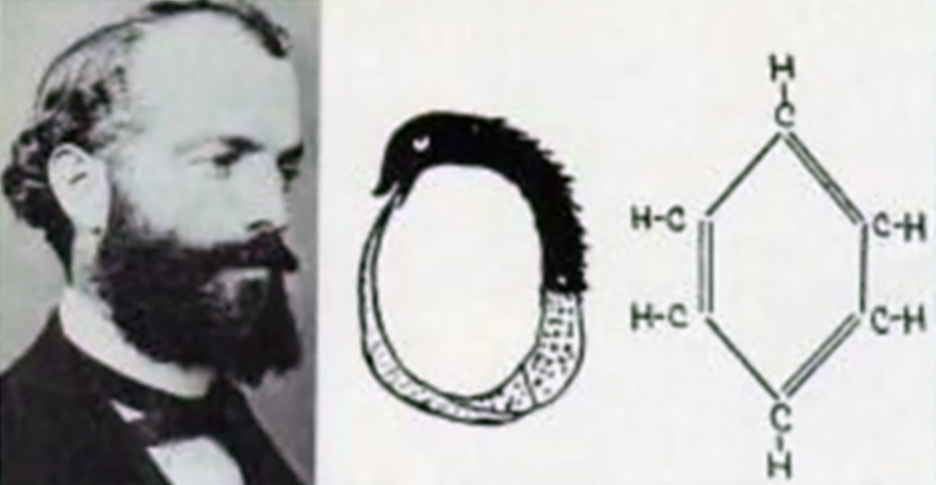

In 1926 Wallas saw creativity as insight, intuition, or inspiration that follows four steps: First, deep focus on a problem over an extended period followed by relaxation and incubation where one’s subconscious mind continues to work on the problem, with a fully-formed solution suddenly occurring to one’s conscious mind as an “Ah hah!” or “Eureka!” moment, a numinous peak experience followed by validation to justify the decision. The story of Archimedes and the king’s crown is a apt example, or of August Kekulé’s discovery of the structure of benzene. Brain research suggests that a section of the right hemisphere called the anterior Superior Temporal Gyrus (aSTG) is responsible for these bursts of sudden insight as new connections are found in the brain’s right hemisphere. The aSTG lights up about 40 milliseconds before the idea reaches the conscious mind.

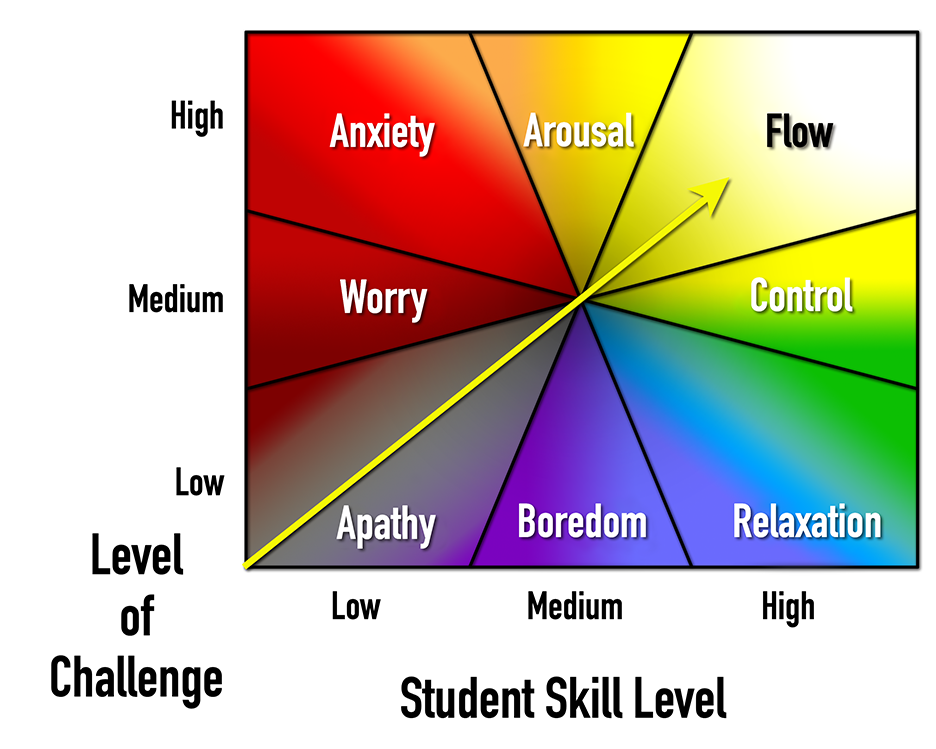

Other theories posit that creativity is a cognitive or mental state, a sequence of thought processes or patterns of thought which include preconditions that can be learned, all adding up to creative acts. Csikszentmihalyi proposed that creativity occurs when a person’s mind reaches a balance between the challenge of a task and the skills or abilities of the person. He called this state flow and it is characterized by effortless thought and a feeling of peak performance where time seems to slip away and the work seems to create itself; it is autotelic because the experience is self-affirming.

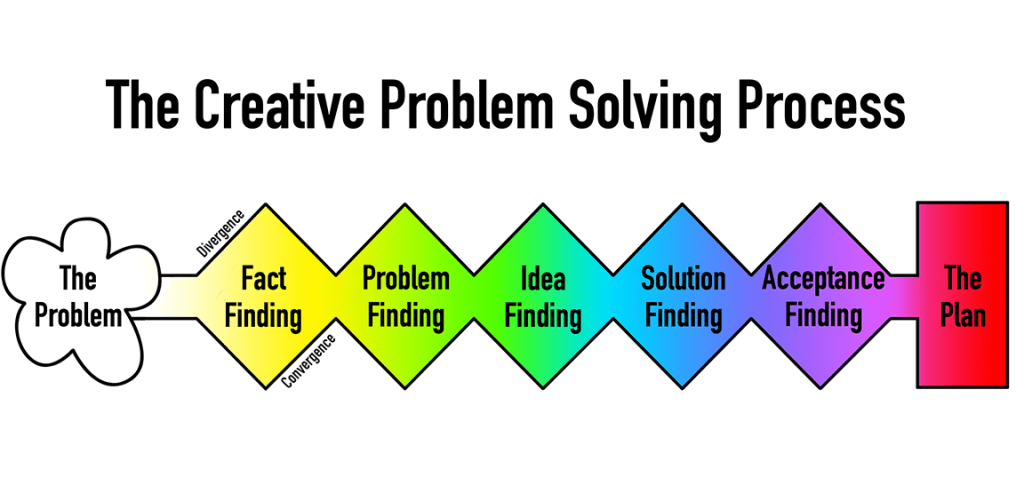

Creativity can be seen as fluency at coming up with new ideas through brainstorming, or overcoming conceptual blocks that prevent us from generating new and unique ideas. It proceeds through a series of divergent and convergent processes; once ideas are generated in an expansive, non-judgmental fashion, they must be evaluated according to criteria for success and narrowed down to a final idea.

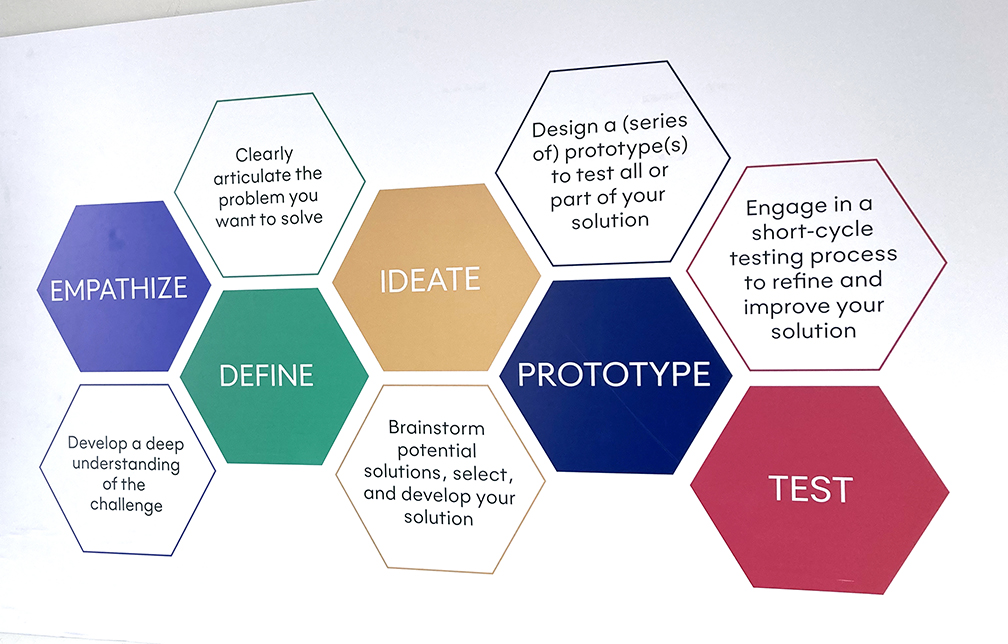

Other researchers see creativity (or innovation) as a process with a series of steps including defining a problem, developing ideas for solutions, choosing the best idea, deciding on a list of required specifications for a successful solution, then designing and building a prototype which is tested and revised until the specifications are met. This process is also called the engineering design process or the design thinking process.

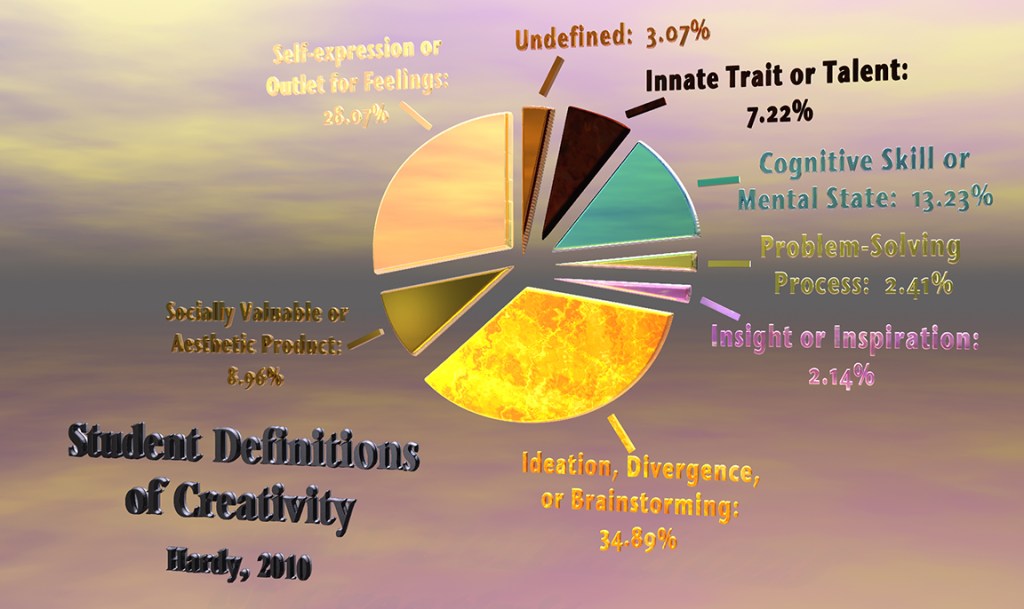

From a social-emotional perspective, creativity can be seen as an outlet for feelings, an opportunity for self-expression, artistry, and fun (Hardy, 2010). Creativity is self-affirming and as the successful production of a creative work, helps to enhance feelings of self-worth and purpose. Instead of having a fixed mindset where setbacks are seen as permanent failures, a creative person recognizes creativity as a process of gradual improvement and growth (Dweck, 2007).

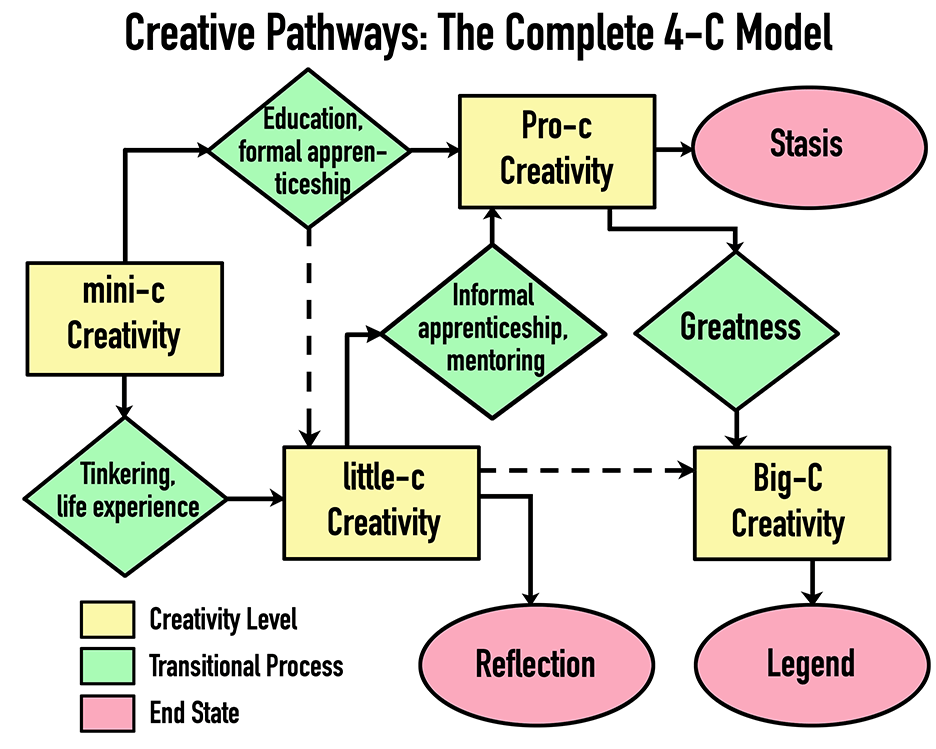

Kaufman and Beghetto (2009) have identified four levels of creativity, including mini-c creativity for learning new things and little-c everyday creativity that all people need to solve personal problems. Some people reach levels of professional expertise and recognition inside of a domain or speciality and are considered to have achieved Pro-c creativity. For the rare few, their creative contributions make history and reach the consciousness of the larger population. Such creativity is called Big-C creativity and is world-changing in scope and impact. It can also be said that if intelligence is multi-faceted, as in Gardner’s theories of multiple intelligences, then there must be a form of creativity associated with each type of intelligence. Those people with linguistic intelligence will show linguistic creativity and an ability or talent for writing or speaking; those with kinesthetic intelligence will demonstrate acts of kinesthetic creativity through dance, choreography, gymnastics, or athletics.

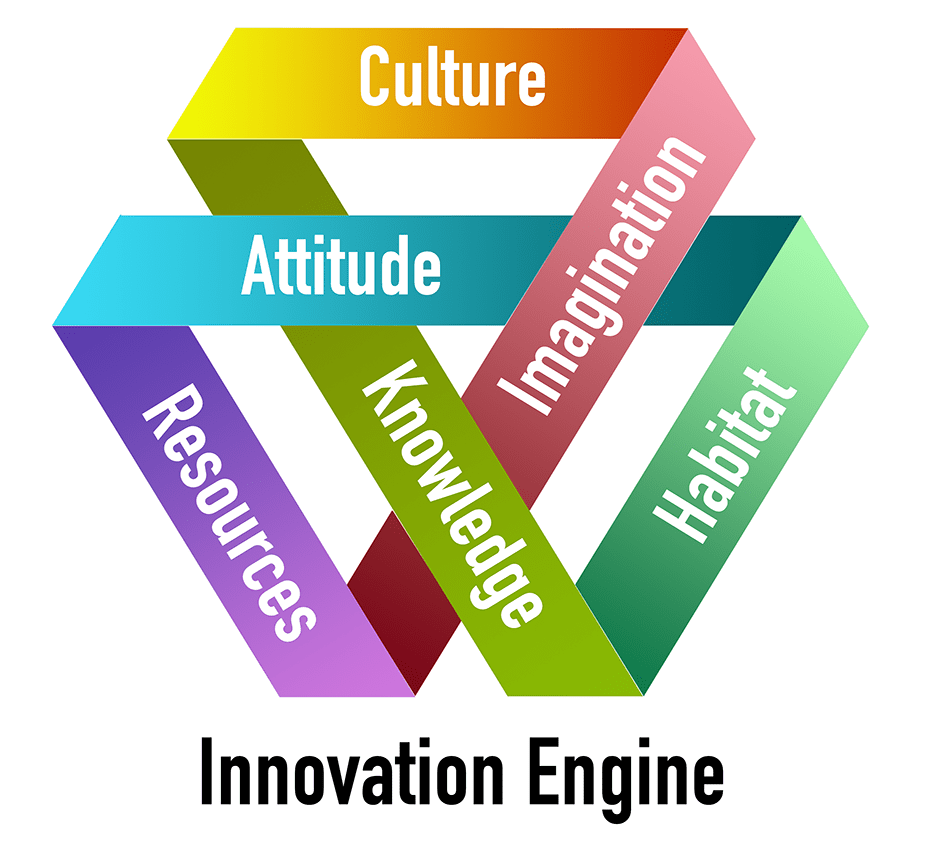

Tina Seelig with Stanford’s Innovation Lab envisions the engine of innovation as a series of three internal factors (imagination, knowledge, and attitude) and three corresponding external factors (habitat, resources, and culture). Innovation requires personal imagination of what can be, knowledge of how to attain it, and an attitude of personal efficacy to reach it, but also requires a supportive environment (habitat), sufficient resources, and a surrounding culture that rewards innovation.

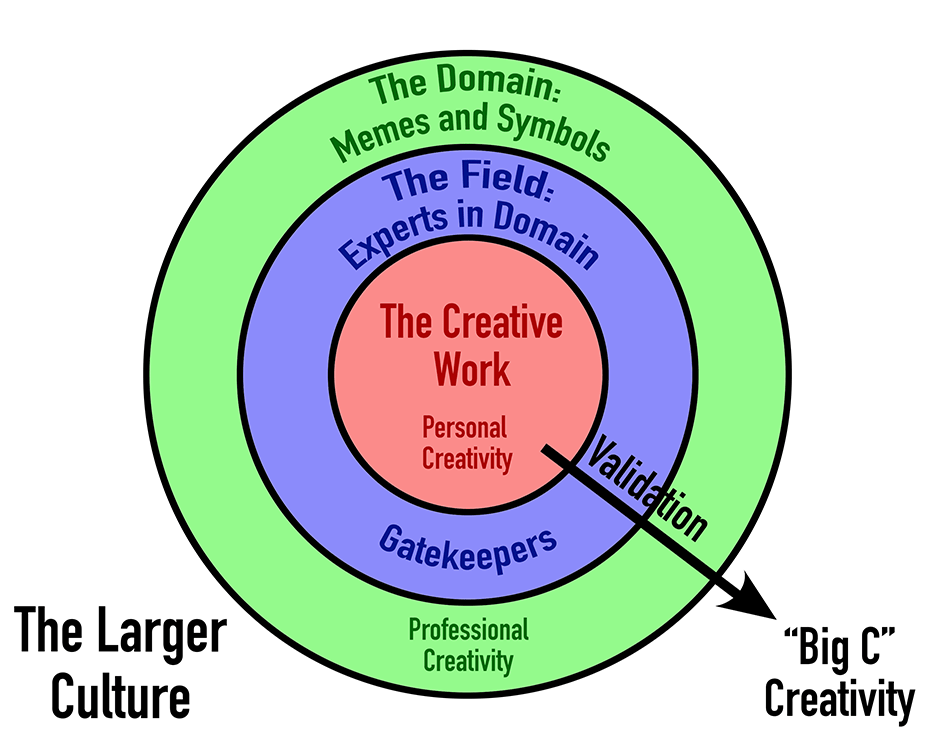

Mihaly Csikszentimihalyi saw creativity as memes which change a domain of study, validated by a field of experts. He felt that just as mutations in genes, as passed on by biological organisms, can lead to evolution, so can memes (ideas, concepts, understandings, or tools) be transmitted through social means from person to person throughout a culture, causing entire domains of thought to shift and evolve. These memes will only be accepted, however, if the social influencers and other experts, who act as gatekeepers, consider the new memes to be valuable enough.

Clapp sees creativity as the evolution of ideas, not as the acts of individuals. When we focus on the biographies of famous creatives, we run the risk of thinking of creativity as only a “great white man” prerogative, inaccessible to underrepresented groups. Through considering creativity as the evolution of ideas, all people from all ethnic groups can contribute equally to new ideas and participate in the socially distributed processes of creativity and innovation.

Barriers to Creativity and the Implications of Theory:

Each one of these theories implies its own possible barriers and limitations. For the ancient concept of the daimon, if a person failed to realize their daimon or genius, or failed to heed the promptings of the Muses, the end was frustration at best and self-destruction at worst. For some, the drive to create is so inescapable that they will forgo sleep or food to pursue their creative impulses. An educational implication, if we use this definition for creativity, is that schools have the responsibility to help students find their personal destinies or daimons, then teach them how to achieve and actualize their potentials while avoiding the destructive side of creativity. If every person were to achieve self-actualization or to reach the inherent potential of their personal daimons (which are unique to the individual), then society will benefit through a commensurability of excellences (Norton, 1976) as our skills and abilities complement each other. As educators we must help all students follow the Greek imperatives.

For creativity as a talent or gift given at birth, the barrier given in the Gospel of Matthew is fear: the unprofitable servant hid the talent and did not try to improve it out of fear of the Lord’s displeasure. Helping students to find their talents, their learning styles, and hidden gifts is therefore a major responsibility of schools and do so with a full acceptance that eliminates fear. A wide variety of types of classes and learning experiences will help students discover and develop their inner voice. As they improve their talents in the world, they will overcome fear and become capable and contributing adults.

If creativity is insight, inspiration, or intuition, then we should set up classes to promote the steps necessary for insight to occur. First, students need to do deep dives into subjects to gain the necessary expertise. They must be allowed to follow their passions, then be provided with challenging problems to solve and the freedom to explore and incubate possible solutions. When insight occurs, we must teach them how to recognize it and capture it in the moment, finding ways to validate their breakthroughs. The barriers to creativity as insight are that sometimes the right solution isn’t something to be found or recognized; there might not be a “right” solution. The insight process might by stymied when no brilliant idea is forthcoming. We, as teachers, have to train students to deal with these no-win situations and the attendant frustration. We must model persistence and resilience.

If creativity is a mental state with preconditions or a balance of challenge and ability, then we need to set up our classrooms with the conditions required for creativity and flow to occur. We have to provide tasks at the right level of challenge for the skills and maturity of our students. Otherwise, if challenge is too high for a student’s abilities, anxiety and frustration will occur. If the task isn’t challenging enough, then boredom and even apathy can result. As tasks become more challenging, so must students’ abilities. Both must grow at the same rate for the optimal balance of creative flow. It is therefore incumbent upon schools to provide more than rote learning of facts; students must practice practical skills along with the steps of problem-solving, collaboration, and communication.

We do a fairly good job of teaching students how to come up with new ideas – that usually isn’t the problem. What can be a problem is allowing the ideas to build on each other without judgment. It is difficult to get students to withhold judgment for ideas they don’t like or agree with, either through negative comments or even body language. Students have to learn to listen, really listen, to each other instead of talking over each other and blurting out whatever comes to mind. Another challenge with creativity as idea fluency is teaching students how to overcome conceptual blocks, especially since they are often completely unaware that such blocks exist. Blockbusting exercises such as the well-known nine dot problem can be effective, but it takes a well-trained discussion leader to see through students’ mental blocks and lead them to greater ideation fluency. As a masters degree student in Organizational Behavior (a whole lifetime and several careers ago), I developed a lesson plan on emergent leadership that required students to pretend they are the crew of the Carob Bean Queen, a cruise ship about to dock in Miami. A murder has occurred on board and the crew has only a short time to solve it. As the group members read through the information they have on the possible suspects, they do not realize that each group member has a slightly different sheet of paper that provides an alibi for one person (except the murderer). They have to pool resources and work together to find the answer. Often, teen students fail to hear the one shy person who has the critical insight that the papers are different. Instead, the group leader often rides roughshod over the person who has made the discovery and the group becomes stymied because they failed to communicate openly.

To teach problem-solving and innovation as a series of steps, my school has created a course based on Stanford’s Innovation Lab that builds through the process of human-centered engineering. Students are working with client organizations to determine a problem, brainstorm possible ideas, decide on a best solution, create a prototype, test it, and present their proposals to the clients at an end of the year in a Shark Tank style event. To teach them the steps of this process, they are given a choice board/ check list that requires a certain number of activities at each step, such as 5 out of 8 possible choices for defining the problem or 7 out of 10 choices for determining the best solution. Groups can choose which of the optional activities to use, but within a proscribed structure. Once they have passed off their required choices for each step, they are allowed to move on to the next, thereby guaranteeing that they are not short-changing their creative process and jumping to an inadequate idea too soon (which is a common problem with teens).

The social-emotional learning aspect of creativity has not been studied much and is an important gap that my research hopes to fill. As I have worked with students at a residential treatment center for girls with severe emotional trauma, I have seen how their innate creativity suffers when they lack the emotional resilience or confidence to take risks or try new ideas. If they become caught up with perfectionism their creativity suffers and they are unable to handle even the slightest setback or perceived failure. This is why I have made use of Ron Berger’s ideas concerning peer critique and revision. The student’s peers are trained to provide kind, specific, and useful suggestions on how projects can be improved, then students are encouraged to revise their projects and present them again. Instead of a one-and-done assignment or worksheet, their projects teach them how to be resilient, to persist, and to grow as learners.

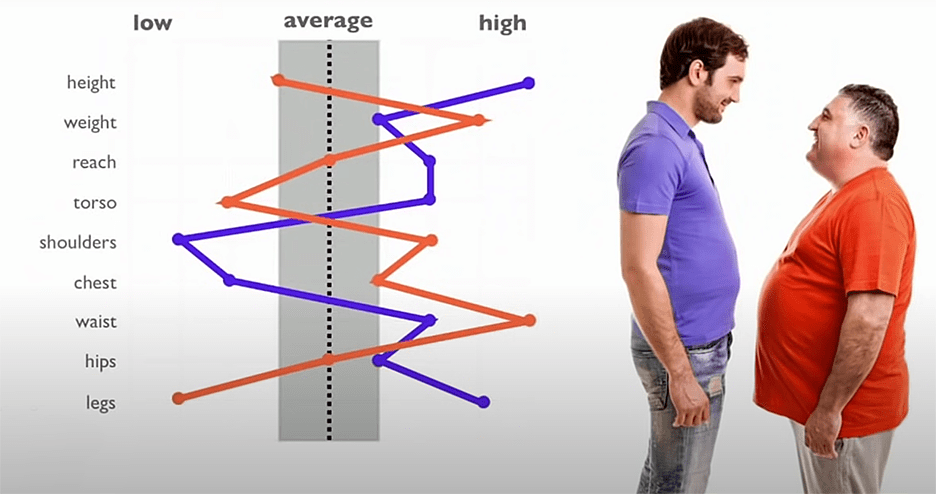

If Kaufman and Beghetto are correct and there is more than one type of creativity (which I certainly believe), then our emphasis on a one-size-fits-all education system will not work equally well with students whose creativity is outside the norm. The barrier here is our inability to adjust and differentiate how we teach creativity. The fault lies with the system, not the student. As I have written about elsewhere, Todd Rose (2016) proposes that creativity, just as intelligence, is multi-faceted and jaggedly distributed. One size does not fit all, nor can any one teaching method reach all students equitably. Forcing students into a bell-shaped curve does them grave injustice. This is why my dissertation research allows for student choice of the topic they pursue, the software they use, and the specific approach or type of media they create. If all students have divergent intelligences and creativities, we must provide the differentiated instruction and choices they need to be successful through the learning styles that work best for them.

For Seelig’s innovation engine model, if any of the six factors are missing, then innovation won’t happen; to achieve classroom innovation, teachers should work on strengthening the internal factors in each child (imagination, knowledge, and attitude) while providing the supportive environment, resources (such as a makerspace or computer hardware and software), and classroom culture that encourages innovation. Since each factor feeds into the next in a kind of continuous Möbius strip, as educators we can work to enhance any one of the six factors and the whole process will improve.

Csikszentimihalyi’s meme theory is an interesting model for looking at creativity’s role in society and how new ideas become accepted. The barriers to creativity become the field of experts who act as gatekeepers and who do not accept the new idea as an acceptable change. Thomas Kuhn spoke of this in his heralded concept of paradigm shifts and revolutionary creativity. Often in a domain of study (such as astrophysics) the field of experts represent an “old guard” that protects the status-quo, blocking any revolutionary new ideas. The only type of creative work allowed is what Kuhn called “normal” science – to conduct experiments that serve to further define and confirm the accepted theory. Some outsider comes up with a revolutionary idea that explains phenomena better and it is unlikely to penetrate the gatekeepers’ blockade. Yet, eventually, the evidence for the new theory becomes too compelling to ignore, and the new idea (meme) becomes accepted as the Old Guard is replaced by the Young Turks.

The implications for education are that educators and universities can be among the most resistant to new ideas. Approval processes such as granting tenure can be used to exclude new and useful ideas that could invigorate a moribund domain. Science has the requirement that theories are always provisional and must be changed in the face of compelling evidence, yet scientists are human and resist change as forcefully as anyone. The solution must be a complete insistence on intellectual honesty. The balance of open-mindedness and skepticism required of an honest scientist is hard to come by, and students must learn to always question dogma and insist on evidence for any claim. They cannot be so open-minded that their brains roll out their ears, but neither can they be so skeptical as to become cynical and resistant to change.

Finally, Clapp’s concept of studying creative ideas instead of creative people leads to an evolutionary, participatory perspective that opens up the creative process to any person without regard to their personal characteristics or demographics. If we are to solve the seemingly intractable problems that face our society, we will need fresh ideas from new sources and cultures we have not traditionally considered; to bring underrepresented people and their ideas into the conversation will be the only way we can find successful solutions and gain essential acceptance. If the problems are global, so must be the solutions. Creativity and innovation must be for all.

Conclusions:

These twelve different definitions of creativity actually lead to some convergent suggestions of how to improve teaching creativity in the classroom. As student voice and choice are of paramount importance for divergent new ideas and for social-emotional learning, one way to teach creativity and problem solving is through project-based learning (PjBL) or problem-based learning (PbBL). Another way is through allowing student choices within carefully delineated structure (choice boards) while providing them with all of the scaffolding and support they need to be successful.

Since self-expression, artistic sensibility, and emotional outlets are deeply entwined with personal creativity, it becomes important for students to learn new skills for artistic and creative expression, such as media design software and fine art skills including visual arts, music, and dance. The A in STEAM is every bit as important as the STEM; the A provides the creative spark that STEM fields are desperately searching for.

Focusing on creative ideas instead of creative people opens up participation for all, as everyone can have creative ideas. As we teach students how to use imagination, intuition, inspiration, insight, and ideation (five important Is), which all students possess, we can enhance their feelings of self-confidence and help them discover and actualize their personal excellences, their unique intelligences and creativities. As we teach them how to balance skepticism and open-mindedness, how to use both creative and scientific modes of thought, and how to achieve and maintain a state of creative flow, they will overcome their feelings of inadequacy in STEM fields as they see that they, too, can make significant contributions.

Finally, as educators and schools, our responsibility is to set up the environment, access to technology, resources, and supports our students need while encouraging them to use and build their imaginations, knowledge, and motivation. Knowledge is important, but teachers are no longer the sole repository of factual information in the classroom. Students who are motivated by challenging, creative, meaningful tasks and projects will dig down for the knowledge, understandings, applications, analyses, and syntheses they need to reach the end goal of personal and social innovation.

We don’t need students who can regurgitate facts. We need students who are creative innovators in all domains of life.

Leave a comment